Five years ago, Beth Fry was a sophomore at The Ohio State University majoring in Public Affairs when she accepted a summer internship at the City of South Euclid. It was here that she and Housing Director Sally Martin began a joint project to dig into the deeper reasons behind what both saw as a mass exodus of white families from the South Euclid-Lyndhurst City School District. Armed with research that Beth had been working on for the past year at OSU, the two began the SEL Experience Project blog to tell the stories of families and students who stayed in the district and to discuss publicly for the first time the statistics and possible reasons behind those who opted out.

As a 2013 graduate of Charles F. Brush High School in the South Euclid-Lyndhurst City School District, Beth saw firsthand the white flight from the schools. “I started noticing it in fourth grade. There seemed to be a lot a fear on the part of parents about sending their kids to the upper elementary school, so many of my friends moved away or were sent to private schools,” recalls Beth. “It wasn’t hard to see that those moving in and those moving out looked very different from each other.”

Beth and her brother Colin attended SEL Schools from Kindergarten through 12th grade. Both went on to prestigious colleges: Ohio State and Cornell for Beth, and Northwestern in Chicago for Colin. Both were at the top of their respective graduating classes at Brush, with Colin being named Salutatorian of the Class of 2015. “Many Brush grads went on to top colleges and have done very well, in many cases much better than our friends who made a big to-do about attending private schools or moving away. I personally have seen little added benefit to those who opted out of SEL, unless it was moving to be closer to family or a desire for religious education. My classmates at SEL and I, meanwhile, received an excellent education while also being immersed in a diverse environment—both racially and socioeconomically—that’s helped prepare us for life beyond high school,” she says. “I remember being a freshman at Ohio State and listening to all my classmates commend the university’s diversity while I was wondering why there were so many white kids,” Beth laughs. “My time in SEL gave me a much different frame of reference.”

Now in 2020, Beth Fry has recently completed her Master of Public Administration at Cornell University. Her thesis, “Racial Imbalance Between Communities and Public Schools in Cuyahoga County, Ohio: Non-Hispanic Whites Opting Out Amid Rising Black Enrollments,” seeks to scrutinize the issue more acutely by analyzing patterns of enrollment and the role of public policy in furthering segregation. Given the current climate of racial inequity in our country and the seemingly futile efforts to combat it, Beth’s findings are sobering and should serve as a wake-up call for policymakers and the public at large.

In terms of school segregation, the clock has gone backward at an alarming rate. Segregation in public schools is now comparable to rates in the 1960s, before court-ordered desegregation plans were mandated across the country. Cuyahoga County has the fifth highest black-white segregation in the nation. 73% of Greater Cleveland’s black residents would need to move in order for the metropolitan area to achieve integration with whites. In the United States more broadly, the Midwest has the dubious distinction of possessing the highest levels of metropolitan school segregation and between-district segregation of any region in the country; much of this is due in large part to discriminatory land use laws and housing policies that actively and legally pushed black Americans into racialized ghettos throughout the twentieth century.

In terms of school segregation, the clock has gone backward at an alarming rate. Segregation in public schools is now comparable to rates in the 1960s, before court-ordered desegregation plans were mandated across the country. Cuyahoga County has the fifth highest black-white segregation in the nation. 73% of Greater Cleveland’s black residents would need to move in order for the metropolitan area to achieve integration with whites.

Tweet

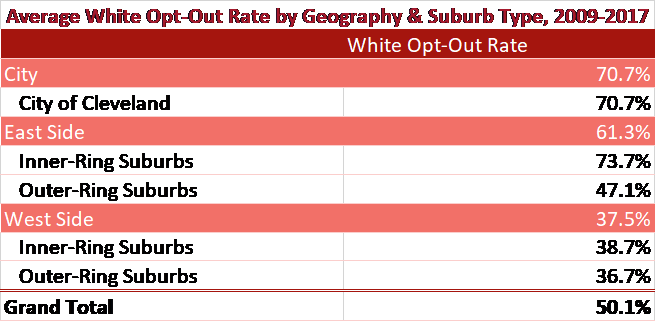

In Cleveland’s east side inner-ring suburbs, the data is particularly alarming. Those communities have a higher number of white families opting out of public schools than those residing within the City of Cleveland. Beth’s data shows that for every two black families moving into these school districts, one white family moves out. East side inner-ring suburbs now have, on average, 78% black enrollment; west side inner-ring suburbs, by contrast, have an average black enrollment of 4% and the City of Cleveland has 67% black enrollment. Between 2009-2017, the white opt-out rate for South Euclid-Lyndhurst Schools was 71%—this refers to the percentage of white families who could use the schools but made other educational choices. In nearby Cleveland Heights-University Heights Schools, which some South Euclid residents attend, a staggering 85% of white families opt-out of the public-school district.

A notable exception to this trend on the east side inner-ring of Cleveland is the Shaker Heights City School District, which has a white opt-out rate of 47%; this is the only east-side inner-ring suburb with an opt-out rate less than 50%. Shaker Heights schools has put forth a notable effort of promoting and managing diversity within the district for decades, and those efforts have obviously been fruitful. To put into perspective just how dire the situation on the east side inner-ring is, the west side suburbs overall have an average white opt-out rate of 38% and the east side outer-ring suburbs have an average white opt-out rate of 47%–the same as Shaker Heights.

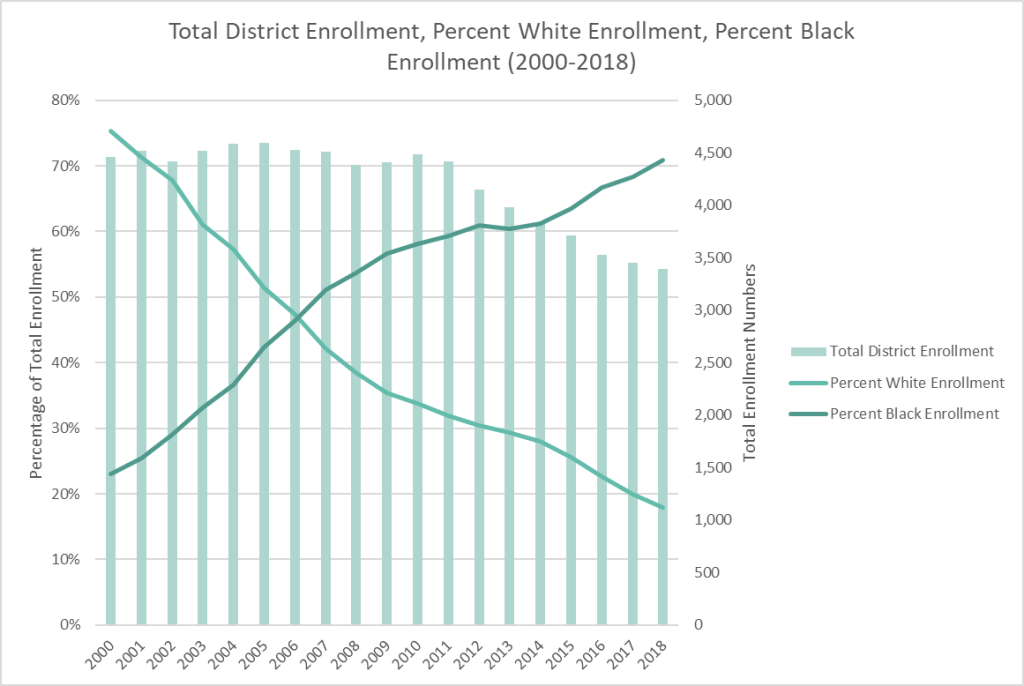

During the last two decades, enrollment in South Euclid-Lyndhurst schools has declined, students qualifying for free and reduced lunch has increased exponentially, and the racial makeup of the schools has dramatically shifted—from 75% white for the class of 2000 to 16% white for the class of 2018.

Given that many of the same faculty, academic, and co-circular programs remain and the district has solid funding, Beth cites recent studies that the changing demographics are caused by white parents’ perceptions of a “racial threat”—the theory that as a minority group increases in size or visibility, the white majority perceives a threat to their security or position of privilege or control. “The difference in white opt-out rates across the county is almost entirely explained by the enrollment proportions of black students in a school district. The higher the percentage of black enrollment, the more white families will seek alternatives for their children to the community public schools,” Beth notes.

Or perhaps it’s the common assumption that high proportions of black students enrolled in a school district is correlated with lower socioeconomic status. Poorer students are assumed to be lacking in parental support and involvement compared to their more financially stable peers, which many extrapolate to mean disruptive classrooms and an adverse learning environment. The irony of all this, of course, is that if white families remained in the district and a balance of racial and socioeconomic diversity was retained, research proves that better outcomes for all students would be assured.[1] “At the end of the day,” Beth says, “most white families will put their own child’s educational future ahead of the long-term, greater good and the advancement of the community, no matter how well-intentioned or verbally supportive of racial justice they may be. But unfortunately, intentions don’t dismantle white supremacy.”

When asked if there is a solution to maintaining a healthy level of racial diversity in schools, Beth cites Louisville, Kentucky as a notable example. “Jefferson County Public Schools are now some of the most racially integrated schools in the United States,” commented Beth. The consolidation of multiple school districts under a federal court order in the 1970s has limited the exit options for parents, requiring them to either move far outside the urban core or invest in private education to avoid attending racially diverse public schools. “It’s part of the reason there’s less segregation now in the South than in the Northeast and Midwest—because school districts are organized at the county level rather than the local level,” Beth stated. Jefferson County Public Schools also implements a method of school choice, where school attendance is based on ranked preference as opposed to neighborhood zoning. The success of the school merger led the City of Louisville and Jefferson County to combine governments in 2003.

In Cuyahoga County, with 59 distinct municipalities and 31 different school districts, schools are still funded by property taxes in spite of the Ohio Supreme Court ruling this method unconstitutional in its 2002 decision in DeRolph v. State of Ohio. [2] This governmental fragmentation is creating an environment of segregation where some schools are “winners” with high standardized test scores and others are “losers” as increasing poverty rates and a loss of diversity results in lower test scores and state rankings—further driving away families who have other options. “Economists and sociologists have linked government fragmentation with increased racial segregation for decades. More school districts and municipalities means more options for white families fleeing desegregation efforts or other proxies for high black enrollments—like state test scores—because smaller units of government make it easier to exclude public good,”said Beth.

This is the ultimate self-fulfilling prophecy. As families are scared away from a diverse district, the district becomes poorer and test scores and rankings drop. The creation of a county-wide school district in Cuyahoga County would require tremendous political leverage and the buy-in of 59 municipalities with home rule powers, a daunting task considering the collective power of suburban communities and the hostility of the state government to the urban core.

When asked about her response to parents citing low test scores and other state metrics for their reasons for opting out, Beth comes back with evidence: “For the past 55 years, research has told us that the greatest predictor of educational achievement is socioeconomic status and parental education level. Only about a third of the achievement gap between white and black students is explained by school quality and classroom characteristics.” Indeed, this is why Beth’s own parents insisted on sending her and her brother to SEL schools. “My parents loosely knew about these findings and that their upper-middle class status put them in a position to make up for any shortcomings in our classroom education, should they arise. My dad regularly helped me as I struggled with my calculus homework and my mom was a mainstay in the PTA up until my brother and I graduated. While some parents may have qualms with using their children as guinea pigs for some form of social equity project, I was one of those guinea pigs and now I have an Ivy League master’s degree.”

Kirk and Hope Fry, a mechanical engineer from small town Indiana and a food scientist from rural Appalachian Ohio, also discussed racial issues with their children from a young age. “I first learned about white flight at the dinner table when I was about 10 or 11,” Beth says, around the time she first started to see a large exodus from SEL schools. “My parents’ decision to stay in SEL despite the massive shift in racial makeup was part of a desire for my brother and I to grow up around people that were different from us, to ensure that we were more comfortable with difference from an earlier age. We often joked that us staying in the district helped ensure diversity as many other white families left. In recent years, they’ve articulated their reasoning for all this as ‘living their values.’ To them, one of the fundamental aspects of loving your neighbor is believing your kids aren’t too good for the schools that serve your community and actively investing in them.” The Frys have been South Euclid homeowners for over 25 years and have no plans of leaving anytime soon.

In the meantime, convincing families that a decision to use their local neighborhood schools is a decision that furthers racial equity can be a difficult argument to make if test scores and state rankings imply that they are providing a substandard educational environment for their children. Arguments that the state testing process is unfair, especially within diverse school districts, are valid, but those are often the only benchmarks that families use to compare districts. Beth further noted that, “Social networks often play a critical role as well, and if yours believe the community public schools with a high proportion of black students is inadequate, you’re likely to make decisions that support that view.”

If we truly want change, and if we are honest with ourselves, we must start with how our children are educated and with whom they sit alongside day after day.

Tweet

The Black Lives Matter movement seeks to call attention to the inequities and injustice that have plagued people of color in our nation for centuries. If we truly want change, and if we are honest with ourselves, we must start with how our children are educated and with whom they sit alongside day after day. As Richard Rothstein, author of the bestselling book The Color of Law, notes in a 2019 article, “Some might argue that ‘a black child does not have to sit next to a white child to learn.’ They are wrong. Not only should black children sit next to white children, but white children should sit next to black children.” Communities like South Euclid and Lyndhurst are in a unique position to be at the forefront of this discussion. Attending school with children of various races and ethnicities fosters understanding and acceptance, and lays the groundwork for enduring equality. More importantly, in a country where black Americans possess a tenth of the wealth of white Americans, diverse schools allow less-advantaged students to have access to the resources of the most-advantaged. Prioritizing school diversity, once a mandate for our nation that has long been abandoned, must again come to the forefront of discussions on creating racial equity. White flight from public schools is an act of covert white supremacy; the time has come for all of us to critically examine our own thoughts and choices, no matter how difficult. Our future depends on it. Let’s get to work.

White flight from public schools is an act of covert white supremacy; the time has come for all of us to critically examine our own thoughts and choices, no matter how difficult. Our future depends on it. Let’s get to work.

Tweet

[1] https://tcf.org/content/report/how-racially-diverse-schools-and-classrooms-can-benefit-all-students/?agreed=1

[2] http://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/DeRolph_v._State_of_Ohio

The link to Beth’s thesis does not work for me. Can you fix the link? The thesis sounds interesting.

LikeLike

We are working on it. It’s on her LinkedIn page and we are planning to move it to Dropbox or Google Docs to enhance access to those not on LinkedIn.

LikeLike